“Madness!! Auditions.

Folk & Roll musicians-singers for acting roles in new TV series.

Running parts for 4 insane boys, age 17-21. Want spirited Ben Frank’s-types. Have

courage to work. Must come down for interview.”

We all know

what happened after this ad was published in Variety and The Hollywood

Reporter in September 1965. Mike Nesmith, Micky Dolenz, Peter Tork, and

Davy Jones may have had varying levels of success “coming down” for their

interviews, but interview they did, and one year later, they could all be seen glaring

out from the cover of their debut album and capering on a new hit series The Monkees, which

debuted on this very day in 1966.

Fifty years

later, The Monkees seem to be as popular as ever, and more importantly, have

finally gotten the critical approval they should have been getting

since Micky first crooned “Last Train to

Clarksville”. For many of us, The Monkees also provided an accessible

introduction to the pop world when we were still a little too young for The

Beatles’ complexity, the Stones’ luridness, or The Who’s violence (yet,

somehow, we were ready for “Writing Wrongs”. Go figure). I’ve been a Monkees

freak for thirty years now, and my obsession with the TV/recording/stage/screen

sensations has left me with a wealth of Monkee facts and figures I am about to

bounce off your million-dollar head in a feature I call…

Here we come...

OK, let’s address the big, smelly ape in the room with our very first entry. So, The Monkees did not form in a garage the way most bands do. They were put together by TV show producers for mostly commercial reasons, to cash in on the ongoing phenomenal success of The Beatles (see B), and to attempt to recreate the irreplaceable magic of A Hard Day’s Night and Help! for boob-tube audiences. This does not mean The Monkees weren’t artists. Micky had done his time in a garage band sometimes known as Micky and The One Nighters, and more coincidentally, The Missing Links, and possessed a voice of magnificent range and dramatics. Peter Tork was a hat-passing folkie with an extraordinary knack for picking up instruments (piano, guitar, banjo, bass, French horn, etc.) that made him The Monkees’ own John Entwistle or Brian Jones-style jack-of-all-trades. Davy Jones had been an acclaimed Broadway song-and-dance man, and Mike Nesmith was a composer, performer, and recording artist. The boys brought their individual talents to a project that didn’t necessarily need and really didn’t want them. By asserting their artistry on records that were going to sell millions whether or not Peter picked his banjo on the sessions, he, Micky, Mike, and Davy made the Monkees’ albums better than was necessary. Consequently, efforts such Headquarters; Pisces, Aquarius, Capricorn, & Jones, LTD.; and Head became albums as timeless as much of what The Monkees’ organically formed peers were making in the mid-sixties.

The guys’ original compositions also made for some of the

most interesting tracks on those records, and we’re not just talking about those of seasoned

composer Mike Nesmith, whose pure country (“Good Clean Fun”, “Don’t Wait

for Me”), pure rock (“Mary Mary”, “Circle Sky”), country-rock (“Sunny

Girlfriend”, “You Told Me”), and country-psychedelia (“Tapioca Tundra”,

“Auntie’s Municipal Court”) were consistently invigorating. Peter Tork’s “For

Pete’s Sake” was strong and vital enough to serve as the series’ closing theme

during season two, and his “Can You Dig It?” and “Long Title: Do I Have to Do

This All Over Again?” helped bring the ultra-hip Head soundtrack to life. Micky Dolenz’s “Randy Scouse Git” was

strong enough to become the first Monkee-composed single A-side (at least in

England where it was retitled “Alternate Title” and went to #2), and his “Mommy

and Daddy” was a piece of unflinching agit-prop aimed at pre-teen revolutionaries.

Even Davy Jones matured into a composer capable of such fine pieces as “Dream

World” and the tough-as-shit “You and I”. Had The Monkees never

expressed themselves as artists on songs such as these, it is likely I would

not be writing about them right now and you wouldn’t care to read about them.

Not only did John Lennon supposedly tell Mike Nesmith that

he never missed their show and considered them to be the best comedy team since

The Marx Brothers, he also befriended Mike, famously inviting him to rub elbows

with fellow luminaries such as Mick Jagger, Keith Richards, Marianne Faithfull,

and Donovan at the recording session for the orchestral crescendo on “A Day in

the Life”. Paul McCartney struck up a similar comradeship with Micky, who

writes delightfully of getting stoned and zoning out to a TV tuned to static

with the Fab one in his autobiography I’m

a Believer. Micky was so taken with his encounter that he name-checked “the four kings of EMI” in “Randy Scouse Git”. A couple of tracks earlier on Headquarters, he name-checked Ringo on

“No Time” in homage to The Beatles’ version of “Honey Don’t” (The Monkees’ discography also abounds in less explicit references to the four kings: Boyce and Hart were inspired to write “Last Train to Clarksville” after hearing the fade out of “Paperback Writer” on the radio; the baroque arrangement of “I Wanna Be Free” was clearly cribbed from that of “Yesterday”; the “Pleasant Valley Sunday” riff is a variation on that of “I Want to to Tell You”; Davy’s “The Poster” was inspired by the circus themes of “Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite”; the false count in to “You Told Me” winks at the one that begins “Taxman”, etc.). In an unprecedented move, The Beatles gave Micky permission to use their “Goodmorning, Goodmorning” in “Mijacogeo”, the Monkees series finale he wrote and directed. Meanwhile, Peter one-upped

both Mike and Micky by actually playing on a session with a Beatle: when George

recorded the soundtrack for the goofy “art” movie Wonderwall in 1968, he called on the Goofy One to contribute his

prodigious banjo talents. Who’s goofy now?

Embodying the role was Henry

Corden, a character actor with a resume that could choke the Monkeemobile’s exhaust pipe. Corden had been a TV staple since he turned up as a deliveryman

on The Life of Riley in 1949. In the fifties he appeared on such shows as The Adventures of Superman, My Little Margie, The Count of Monte Cristo, Soldiers of Fortune, Perry Mason, and Dragnet. In the sixties, he was

even more of a living room presence, showing up on Peter Gunn, 77 Sunset

Strip, Wagon Train, The Twilight Zone, The Untouchables, Jonny Quest, I Dream of Jeannie, Mister Ed, and Gilligan’s Island. He also flaunted

his vocal talents in a number of roles on The Flintstones, which sparked a

major sideline for the actor in cartoons. In fact, with 1977’s A Flintstone

Christmas, Corden actually took over the coveted role of Fred Flintstone from

the recently deceased Alan Reed, who’d originated the character on the sixties

series. Fred was a big feather in Henry Corden’s cap, but Monkees fans will

always remember him best as rotten Mr. Babbit… and, to a lesser extent, the slightly less-rotten hotel manager Mr. Blauner (see R) in the post-Babbit episode

“The Wild Monkees”.

Everyone knows that The Monkees are Mike, Micky, Davy, and Peter. Well, except when they’re Mike, Micky, and Davy. Or Micky and Davy. Or Micky and Peter. Or…bah-dum…here I come, walking down the street, I get the funniest looks from, everyone I meet…Hey, Hey, I’m a Monkee…

As has been the case with The Threetles (Paul, George,

and Ringo without John) or The Two (Pete and Roger without John and Keith), The

Monkees have not always been a foursome. In fact, for the majority of their

career, they were not really a foursome. Even on their only true “we’re a

band!” record, Headquarters, Chip

Douglas, Jerry Yester, and John London regularly contributed bass tracks that

swelled their ranks to a quintet. On their first two albums, it was rare to

have more than one Monkee on a single track. However, the band was always seen

as a foursome... at least for their first couple of years.

The first to jump ship was Peter, when he bought himself out

of his contract in late 1968 after shooting the last-gasp TV special 33⅓ Revolutions Per Monkee. When the next album, Instant Replay, was released less than two months later, Peter was

absent from the album cover, though his guitar and Danelectro bass work were

actually buried within Mike’s wall-of-sound production of an old track from the

Monkees-’66 archives, “I Won’t Be the Same Without Her”.

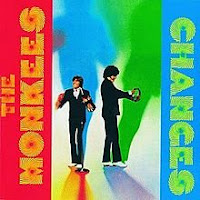

After the next album and a notoriously odd tour with a

lounge R&B band called Sam & The Goodtimers (see T), The Monkees shed another member, reducing the act to a duo of Micky and Davy. Without the two

most dominant musical forces in the band, The Monkees made their final album as

they made their first two: leaving the music completely in the hands of a

producer (tin-pan alley hit-maker Jeff Barry). Consequently, Changes was the most bubblegum and least

experimental record the guys ever made. It is telling that the band’s most bubblegum

and least experimental member, Davy, basically disowned the record, though it

had Micky’s relatively un-bubblegum and experimental C&W ramble “Midnight

Train” going for it. After that came a flop Micky/Davy single, “Do It in the

Name of Love” and the end of The Monkees’ classic years, but not the permanent end

of The Monkees. 1986 saw a major twentieth-anniversary Monkees revival (see P) that found the guys back on the road

playing to sell-out crowds and releasing their first top-twenty hit since “D.W.

Washburn”. But not only was serial hold-out Mike Nesmith not on that record,

Davy was missing too because of his bitterness over how Arista records had

handled his seventies solo career when the label was still called Bell Records

(see X). This left vocalist Micky

and guitarist Peter as the only Monkees on “That Was Then, This Is Now”. Davy

pointedly left the stage whenever his band mates performed the hit on stage.

In the years to come, The Monkees almost always worked as

less-than-four, with the sole exception being 1996’s Justus album, the only Monkees LP cut without any outside input.

However, even its companion tour was a case of the missing Monkee as Mike fled

after receiving some bad notices from the British press. Sadly, Davy’s death in

2012 guaranteed that all future Monkees ventures would always lack involvement

from the four individuals… which, in a strange and sad way, is kind of true to

how the guys made music for most of their existence.

Taking The Monkees seriously was a mistake “serious” music

journalists never dared make during the band’s heyday. They were posers to be

scoffed at and mocked. Their music was chart-clogging puffery. Their image was

family-friendly counterrevolutionaries. They symbolized the crassest, anti-art

corners of capitalism. Blah blah. Then in 1985, a writer named Erik Lefcowitz bravely stood up and said,

“I’ll take ‘em seriously!”, publishing the first serious look at The Monkees, The Monkees Tale, through hip San Fran

publishers Last Gasp. Sure the book was slim as a CPR leaflet. Sure, Lefcowitz

didn’t seem to actually like The Monkees that much. But it was a watershed

moment, and I’m sure more than one aspiring pop writer decided to become an

aspiring pop writer after reading The

Monkees Tale (I know I did).

In the years to follow, serious reevaluation of The Monkees

ceased to be an embarrassment. One Monkees historian, Andrew Sandoval, actually

really loved the band and wrote the first truly great and exhaustive Monkees

book: 2005’s The Monkees: The Day-by-Day

Story of the 60s TV Pop Sensation. Lefcowitz subsequently fattened out The Monkees Tale a bit more (though

seemed even less impressed by the band than he was in ’85) and republished it

as Monkee Business in 2013.

Meanwhile, other serious studies of The Monkees continue to pop up in books

such as Rosanne Welch’s Why the Monkees Matter: Teenagers, Television and American Pop Culture and Peter Mills’s upcoming The Monkees, Head, and the 60s or sites such as The Monkees Live

Almanac and Monkees.net, which counts the original Monkee scholar, Eric

Lefcowitz, among its contributors. Most of these print and online publications were valuable resources in the creation of this very feature you’re reading right now!

The Monkees can count making hippies family friendly among their myriad accomplishments. Fortunately, the older generation was pretty clueless, otherwise they might have understood why the guys’ eyes were so red, why they kept giggling for no reason in “The Monkee’s Paw”, and why the Frodis alien in “Mijacogeo” mostly consisted of a plant that mellowed out the villains by emitting plumes of fragrant smoke. Yes, The Monkees were big potheads (even sweet little Davy!), and Frodis was their code name for the demon weed. According to Dolenz, he derived the word from the name of everyone's favorite weed-smoking hobbit, Frodo Baggins, a favorite mascot of the hippie culture. In fact, Mick could sometimes be seen sporting a "Frodo Lives" badge.

As is obvious from the episodes mentioned above, the guys

did not keep their pot consumption to off-business hours (not that The Monkees

had many of those), and even had a refrigerated room dubbed “The Black Box” installed

on set for them to puff their brains out between takes while filming their

show. Despite how seemingly blatantly The Monkees flaunted their indulgences—their

one and only movie was called Head

for the love of crimony!— they were strictly instructed to never let on about

their drug use in interviews, and would cheekily taunt over-inquisitive

journalists by claiming they were hooked on Ex-Lax.

With fame comes parody, and few bands were as famous as The

Monkees in the sixties. However, there wasn’t a great Monkees parody of note

until 1992, the year that young people across the U.S. adapted disaffected

poses and swathed themselves (OK, fine, ourselves)

in unflattering baggy sweatshirts, flannels, ripped jeans, and combat boots.

Comedian Ben Stiller recognized the faddishness of grunge and spoofed it

by imagining four Seattle twangers living together in a laugh-track-haunted flat

and enjoying surreal adventures, trying to impress a record exec, joining arms

to do “the walk,” and getting starry eyed at the sight of cute grunge chick Goo

(Jeanne Tripplehorn channeling Kim Gordon). Hey, hey… Jonsie (Stiller), Dolly

(Andy Dick), Stone (Bob Odenkirk), and Tork (Jeff Kahn) are The Grungies, a spot-on parody of Gen-X

bullshit and The Monkees that appeared on the short-lived, fondly remembered

sketch comedy series The Ben Stiller Show. Adding extra

legitimacy to an already hilarious sketch, record exec Josh Goldsilver is none

other than a smarm-oozing Micky Dolenz.

Boyce & Hart may be best known as Monkee handlers, but

they had a prolific career outside of that multi-media project. In their

pre-Monkees days they were responsible for The Goodies’ “Dum Dum Ditty” (best

known by The Shangri-La’s later version) and Jay and the Americans’ “Come a

Little Bit Closer” (co-written with Wes Farrell and the song that caught Don Kirshner’s golden ear). Bobby also co-wrote Little

Anthony’s gut-wrenching smash “Hurts So Bad” with Teddy Randazzo and Bobby

Weinstein. And before The Monkees took a crack at “Steppin’ Stone”, Paul Revere

and the Raiders had first dibs on it with a slightly less renowned version on

their Midnight Ride LP.

Boyce & Hart also had a pop career of their own,

starting as the frontmen for The Candy Store Prophets, whose Gerry McGee

(guitar), Larry Taylor (bass), and Billy Lewis (drums) played on their share of

Monkees sessions (especially ones for the first album). They also had a

well-deserved top-ten hit under their own names in 1968 with the exhilarating

“I Wonder What She’s Doing Tonight”.

Five years after the official dissolution of The Monkees,

the duo who saw it out the longest became a foursome again when Micky and Davy

recorded and toured with Tommy and Bobby as Dolenz, Jones, Boyce, & Hart.

Ironically, their only album was not exclusively stacked to the gills with Boyce

& Hart originals, although it did contain two landmark Dolenz/Jones

originals.

At the end of the decade, Tommy Boyce reemerged with his own

group, The Tommy Band. Bobby also recorded his solo debut, titled, rather

appropriately, The First Bobby Hart Solo

Album. In the mid-eighties both composers reunited on stage to tap into the

renewed fascination with The Monkees (see P).

Sadly, Tommy Boyce also suffered from physical and mental health issues and

took his own life in 1994.

Bobby Hart, however, lived to tell his tale in last year’s Psychedelic Bubblegum: Boyce & Hart, The

Monkees, and Turning Mayhem into Miracles, and naturally, when Micky,

Peter, and Mike reunited earlier this year to record their first album in

twenty years, Good Times!, they were

compelled to finish off “Whatever’s Right”, a Boyce & Hart tune left

unfinished since 1966. After all, it wouldn’t be a Monkees album without at

least one Boyce & Hart tune.

Lugging around equipment is the bane of the musician’s

existence (I once regretfully passed on a groovy ’68 Volkswagen Beetle because

I couldn’t fit my bass and amp into its tiny trunk). Fortunately for The

Monkees, they had a cushy ride they dubbed the Monkeemobile to transport their

Gretsches to gigs. This was key since a band that had so much trouble getting

auditions and record deals could hardly afford roadies. Don’t ask how they were

able to spring for a custom GTO though. That will have to remain yet another

mystery of Monkeeland.

Less mysterious is the history of the Monkeemobile. It is

the handiwork of Dean Jeffries, the

Hollywood stunt coordinator and car customizer tasked with making wheels for

Mike, Micky, Davy, and Peter. Jeffries’s buddy Jim Wangers was doing promo with

Pontiac at the time and figured there was no better way to get his product in

front of car buyers than to feature it every week on a network sitcom. He

furnished Jeffries with a couple of 1966 GTO convertibles, and the dude got to

work dropping in a bench where the trunk had been, extending the tail lights,

installing a parachute on the rear, and doing other modifications that

transformed these vehicles into Monkeemobiles. As a slick bonus, the real Mike,

Micky, Davy, and Peter got their own GTOs.

The Monkeemobile was rarely a major player in the series,

though Micky could sometimes be seen working on it. However it was always group

leader Mike who got to drive it…perhaps not the wisest decision since Mike was

known to rocket his own GTO down the Hollywood Freeway at speeds up to 125mph. The

car only really got to shine in season two’s “The Monkees Race Again” when it

was pitted against the Klutzmobile, piloted by a couple of Hogan’s Heroes

rejects.

Shortly after that episode aired, The Monkees was no more,

and the Monkeemobile ended up in the possession of George Barris, who had his

own impressive automotive pedigree as the designer of the Batmobile and the

Munster Coach. In 2008, Barris auctioned off the Monkeemobile to a private

owner who is no doubt driving it to auditions and gigs all over Michigan.

To be clear and fair, Kirshner wasn’t really a villain, and

he wasn’t even a bad guy. As the music supervisor on the whole “Monkees” project,

he actually did a very good job bringing in Tin Pan Alley hit makers to supply

the series and its accompanying soundtrack discs with catchy pop tunes. Kirshner

even helped The Monkees get a major hit before the series went on the air.

Kirshner’s problem was that he lacked flexibility and refused to recognize the

talent or ambitions of the young men playing a phony band on TV. It would be

one thing if Mike, Micky, Davy, and Peter lacked a feel for pop music or

experience in the business, but they really were fine musicians, performers,

singers, and composers. When Mike understandably reacted against the

critical drubbing he and his cohorts were receiving for not functioning as a

“real” band (a pretty unfair expectation of the press in any event), he

demanded that he and the other guys play on their records (a businessman as

well as an artist, Mike also surely realized the money-making potential of getting

more of his own compositions on Monkees vinyl). Kirshner, an old-school record

industry bigwig, saw this as insubordination and lack of gratitude from a

sitcom actor.

Had this conflict occurred a couple of years earlier, the

trophy surely would have gone to Kirshner, but 1967 was a turning point that

found young people, particularly young musicians, being taken more seriously.

Plus, "The Monkees” was a hit and the project’s producers were afraid Mike would

make good on his threat to walk if he didn’t get his way. Amazingly, these four

guys who barely had any experience playing together would be allowed to cut

their own records, and the first would be a single B-side slated for early ’67:

Mike’s “The Girl I Knew Somewhere”.

Kirshner had other plans and issued back-to-back songs by proven hit makers

Neil Diamond and Jeff Barry recorded after coaxing the rather

counterrevolutionary Davy Jones into the studio. This act of insubordination earned Kirshner the heave-ho, and The

Monkees were now in charge of their own recordings.

The following year, Kirshner found a band more likely to

follow orders: cartoon characters The Archies. Their #1 smash “Sugar Sugar”

must have tasted like sweet victory to Kirshner since it far outsold any

Monkees single of ’69 and because he claimed he’d pitched it to The Monkees,

who rejected it (Jeff Barry says this is a myth). Kirshner continued to enjoy

success as the host of Don Kirshner’s Rock Concert in the seventies, though

his bitter feelings about getting canned from the “Monkees” seemed to last

until his death in 2011.

Like any hit-racking band or landscape-changing TV series, that thing called “The Monkees” left paw prints running up and down the pop culture terrain. The Monkees may not have been TV’s first pop singers (Hiya, Ricky Nelson! How you enjoying your chart success, Shelley Fabares? Umm, good for you, Paul Peterson), but they were its first band of any note, and it would be wrong to fail to recognize their influence on The Partridge Family, The Heights, Josie and the Pussycats, The Banana Splits, and of course, The Archies (see K), even if, as far as legacies go, it’s not the most dignified one. More agreeably, actor Walter Koenig has claimed that the popularity of Davy Jones inspired Gene Roddenberry to add his own diminutive mop-top, Mr. Chekov, to the Star Trek crew. Nevertheless, The Monkees were always strongest on record, and the future artists who grew up digging their music is impressive: The Bangles, Tom Petty and The Heartbreakers, The Go Gos, R.E.M., XTC, Guided by Voices, Nirvana, U2, Weezer, among scores of others. Several of these artists even contributed material to Good Times!

The Monkees’ legacy

can also be felt in the bands who chose to play their music. The songs they

made famous have been covered by Robert Wyatt, The Sex Pistols (can we agree

they were playing tribute to The Monkees and not Paul Revere and the Raiders...especially since Malcolm McLaren's assembling of The Pistols was so similar to the way Rafelson and Schneider put together The Monkees?),

The Four Tops, Bong Water, The Violent Femmes, The Specials, U2, They Might Be

Giants, The Replacements, The Church, Magnapop, The Wedding Present, and many,

many more. Samples of Monkees music

have driven records by Run DMC, De La Soul, and Del the Funky Homosapien. And during an era

many agree to be a new golden age of television, their songs have returned to

the small screen on some of the very, very best series of the twenty-first

century. On Mad Men, Don Draper pondered his ever out-of-control life to the

swirling strains of “Porpoise Song” (and earlier that season, a character with the last name Torkelson was introduced. Coincidence?). On Breaking Bad, Walter White cooked up

a batch of meth to the pounding “Goin’ Down”. Now that’s a legacy.

When he ceased to find a place on The Monkees, Landis

never exactly had to go begging for work, as he turned up on Hawaii Five-O, McMillan & Wife, Columbo, and Police Woman, as well as features such

as Young Frankenstein, Body Double, Pee Wee’s Big Adventure, and (a-hem)

Candy Stripe Nurses. He still looks

back fondly on his Monkees days, recalling a particular rapport with fellow

UK vaudevillian Davy Jones. Monte Landis hasn’t appeared on TV since showing up on the short-lived Golden Girls spin-off The Golden Palace back in 1992, but at age 83, the devil is still very

much with us.

Head may have

flopped upon release, but the edge that Nicholson brought to the project helped

it become an enduring cult classic for Monkees freaks and people who think they

suck alike. Nicholson’s anarchic wit and sardonic tone, best embodied by his corrosive

“Ditty Diego”, is a constant presence in the film. Nesmith, for one, has

claimed the film was more Nicholson’s vision than that of

co-writer/director/producer Rafelson, and had such lingering fond feelings that he dedicated his biggest solo hit, “Joanne”, to Nicholson and his girlfriend Mimi Machu (the woman who makes out with all four Monkees at the beginning of Head). Tork, whose relationship with Rafelson

was apparently pretty sour by this point, added that Nicholson’s presence made

the filming bearable.

Even without its TV-connection, the “Monkees” project was like no other. Recording went on nearly constantly throughout its brief duration, as hungry composers and producers vied to get their work on guaranteed hit albums. The fact that these producers had four guys to choose for their sessions probably didn’t hurt either. Maybe Boyce & Hart were recording with Micky in one studio, Neil Sedaka and Carole Bayer had Davy in another, Peter was crooning for Jeff Barry and Jack Keller down the hall, and Mike was singing on his own session elsewhere. Consequently, there are tons and tons of outtakes for which there simply could not be room on the group’s nine albums.

With all the material recorded for the first two Monkees

albums alone, twice as many LPs could have been assembled. Several of these

outtakes (“All the Kings Horses”, early versions of “You Just May Be the One”,

“I Wanna Be Free”, “Words”, “Valleri”, and “I’ll Be Back Upon My Feet”) ended

up on the series’ first season to keep the soundtracks from being overly

reliant on the mere two-dozen songs that had been properly released thus far. With

a sole producer (Chip Douglas) at the helm for Headquarters and Pisces,

Aquarius, Capricorn, & Jones, LTD., the sessions were more focused and

the outtakes far less plentiful, but the glut resumed as soon as Mike, Micky,

Davy, and Peter began producing their own sessions after Pisces. So The Birds, The

Bees, & The Monkees became another project with an excess of material. There

were so many recordings at music supervisor Lester Sill’s disposal that he

assembled the seventh Monkees record (Instant

Replay) as a veritable outtakes compilation, mingling some of the earliest

recordings (“Tear Drop City”, “I Won’t Be the Same without Her”) with some of

the latest.

Decades after the whole operation had folded, Rhino Records

took over and started dusting off the plethora of tracks that were denied

release during their own time. The first compilation, Missing Links, appeared in 1987, and while it was not consistent

enough to crown a “revelation”, there were some truly wonderful tracks,

particularly the intended single “All of Your Toys”, Nesmith’s wistful Birds remnant “Carlisle Wheeling”, and

his earlier production of Goffin & King’s “I Don’t Think You Know Me”. Such

pieces have inspired endless fan debates about how records such as More of the Monkees, Birds, and Instant Replay could have been improved with keener track

selection. Swap out “The Day We Fall in Love” and swap in “Of You”… now there’s

a More of The Monkees that would

never make me want to slap the needle off the vinyl!

That first Missing

Links disc was just the beginning, as Rhino rolled out two more volumes,

supplemented the Listen to the Band

box set with several exclusive tracks, and filled out its CD reissues of the

proper albums with leftovers. Astoundingly, there was still enough material to

pad out those albums even further for Rhino’s ongoing series of Super Deluxe

handmade box sets. I still suspect that there are a few more versions of “I

Don’t Think You Know Me” and “Prithee” somewhere in the can.

Quotable catchphrases are natural byproducts of classic TV

series. The Monkees was no different. Who among us has not retorted “I am

standing!” after being commanded to stand up? Who has not sneered “Don’t do

that!” after being the victim of a doing we have not wanted done? Who has not

shrieked “Take that, Wizard Glick!” before smacking the nose of someone named

Wizard Glick? Who has not trumpeted “Frodis!” when requesting a second helping

of marijuana? Our most socially conscious brethren have clearly wailed

“Save the Texas Prairie Chicken!” from the sidelines of protest marches through

the ages. Just this morning you noted the absence of a loved one by breathlessly gasping “He’s gone!” and “Isn’t that dumb?” would be an appropriate thing to say in nearly a half dozen possible scenarios, which is why you’ve said it. Such exclamations reveal how thoroughly the Monkees influence has

crept into each and every life of every man, woman, child, and prairie chicken

on Earth.

Even as The Monkees took television hostage, Rafelson and

Schneider still intended to ride that success into cinemas. Unfortunately,

their first feature production, Head

starring The Monkees and co-written and directed by Rafelson, was a flop of

monumental proportions. Their follow up, Easy

Rider (which they hoped to promote as “From the Guys who Gave You Head”

before realizing the joke would fall flat since no one actually saw Head), was not. Following that film’s

success, Rafelson and Schneider welcomed Screen Gems producer Steve Blauner, who’d worked closely with The Monkees, into the fold,

and Raybert became BBS Productions.

Of course, Rafelson and Schneider would not be best known

for Five Easy Pieces or The Last Picture Show. They would always

be known as the guys who'd created one of the hugest and longest-lasting pop

sensations of the sixties. Not that Bob and Bert always had an easy relationship with that

legacy or the guys. Schneider was unable to comprehend why his partner would

want to make a feature film starring The Monkees. Peter Tork has enduring bitter

feelings about Rafelson, which resurfaced when the Criterion Collection

released a BBS box set in 2010 and public discussion turned to Head, which Peter criticized as a

product of Rafelson’s cynicism. Jack Nicholson claimed that Rafelson specifically set out to end The Monkees with Head.

Yet the movie is largely sympathetic to The Monkees’ plight,

showing that they were a killer live band in spite of accusations that they

couldn’t play their own instruments (see I)

and the unfairness of the series’ depiction of Peter as “the dummy.” Fifty years down the road, Head stands as a surprisingly

humane—and audaciously inventive—portrait of Monkeemania. With the end of BBS’s

seventies success, Rafelson and Schneider both backed off of film considerably.

Bert Schneider died at the age of 78 in 2011. According to Andrew Sandoval, Schneider professed his love for the group and project he co-created shortly before his death.

Mr. Schneider’s wise and calming presence was supposedly a

substitute for the manager character who didn’t sit well with test audiences

(see C). Despite Mr. Schneider’s

multitudinous admirable qualities, one must wonder how Bert Schneider (see R) felt about being the namesake of a

big lump of wood. And despite being the only guy in the pad who was working,

you could not count on Mr. Schneider to cough up a lousy buck-eighty to pay for

an important telegram. Nobody’s perfect.

Considering all the guff The Monkees got for not being a “real” band, you’d think they’d get some credit for putting their careers in jeopardy by demanding they be allowed to become a real band that played on their own records (see K). Sadly, this was not really the case… at least not until more recent reevaluation of the band’s worth.

That initial backlash was actually unfair from the get go,

since The Monkees played as a live band from almost the very beginning of the

project’s existence. Less than three months after The Monkees debuted, The

Monkees were on tour across the U.S.

as players of guitars, bass, drums, keyboards, and maracas (see I). They walloped audiences with pure

Monkee performances of hits such as “Last Train to Clarksville”, “I’m a

Believer”, and “Steppin’ Stone”; LP cuts such as “Mary Mary”, “I Wanna Be

Free”, and “Sweet Young Thing”; and oddities such as “She’s So Far Out She’s

In”, “If I Could Shimmy Like My Sister Kate”, and “Prithee” (see O). They may not have been the most

polished band in the world, but they had plenty of garage band spirit. The

Candy Store Profits (see H) provided

a bit of professional polish as the backing band during solo spots in which

Peter played wicked banjo on “Cripple Creek”, Mike freaked out on the maracas

while howling Willie Dixon’s “You Can’t Judge a Book By the Cover”, Davy did

his Broadway thing on “Gonna Build Me a Mountain”, and Micky did his epic James

Brown impersonation while shrieking Ray Charles’s “I Got a Woman”. Key moments

from the tour were incorporated into Bob Rafelson’s documentary-like “Monkees

on Tour”, one of the most compelling and unique episodes of The Monkees.

After completing their most complete artistic statement, Headquarters, The Monkees were back on

tour with better material and more confidence than ever. Infamously, Jimi

Hendrix opened for several shows on the tour before storming off in frustration

over a teenybopper audience not quite ready for his Stratocaster humping. As

for The Monkees’ portion of the tour, some of it would be captured on the first

official live Monkees album released twenty years after the fact: Live 1967.

In the fall of 1968, The Monkees would traverse other

corners of the world, visiting Australia and Japan with more recent material

such as “Salesman”, “Daydream Believer”, “D.W. Washburn”, and “Cuddly Toy” in

the set list. This would be their final tour with the now bearded Peter Tork,

but not their final one of the sixties. In 1969, Mike, Micky, and Davy resumed

as the front men of Sam & The Goodtimers, a lounge R&B band who backed them

on an extensive tour from March through December. Critics were baffled by the

combination of Monkees pop and Goodtimers soul. They apparently hadn’t been

paying close attention to a band that often traveled an unconventional road. Don’t

even get me started on the 1987 tour with Weird Al.

1986 was the year The Monkees returned with a vengeance, commandeering MTV (see P), the charts (see “That Was Then This Now”), and the stage as if it were 1967 all over again (assuming everyone wore mullets and played keytars in 1967). With so much cash-making potential, one probably can’t really blame Columbia Pictures Television for trying to slip an updated version of The Monkees past fans new and old. The big surprise was that New Monkees was a smashing success, the series’ wacky comedy and wonderful music becoming as beloved by critics as the stars were by second generation Monkeemaniacs, who unanimously agreed that Mike, Micky, Davy, and Peter couldn’t lick the boots of new idols Jared, Dino, Marty, and Larry.

Wait a minute. No… that’s wrong. Actually, New Monkees

was a colossal failure, croaking after just thirteen episodes (22 had been

planned for season one). Its accompanying album sold about three copies. But

everyone loved The Monkees in ’87. What the hell went wrong? Well, first of

all, there were no actual Monkees in New Monkees. The Powers That Be

seemed to underestimate the fact that wacky adventures were just a small part

of why everyone had become so re-enamored with the original Monkees. We loved the

guys—the real guys. Bringing the original foursome together was a

lightning-in-a-bottle moment for Bob Rafelson and Bert Schneider, and it was a

bit presumptuous to assume that kind of thing could be done twice, even if old

Raybert partner Steve Blauner (see R)

helped produce the new project.

I personally think another factor in the failure of The New

Monkees was the fact that, for many of us, The Old Monkees were a welcome

antidote to the off-putting synthetic atmosphere of eighties pop. After being

force fed a steady diet of Starship, White Snake, Bon Jovi, Debbie Gibson, and

Phil Collins’s Genesis, those old, organic productions by Mike Nesmith, Boyce

& Hart, Chip Douglas, and the rest sounded wonderfully, invitingly real… a

delightful irony considering The Monkees’ reputation for being ersatz. Instead

of trying to tap into that sound, The New Monkees sounded as synthetic and

contrived as Mr. Mister. After suffering through the pilot episode and failing

to feel that old Monkee magic, we tuned out, put Headquarters on the turntable, flicked on the VHS copies of

“Mijacogeo” we taped off Nick-at-Nite, and never looked back.

Valerie Kairys has come to be known as the “Monkees Girl”

because of her starring role in “A La Mode” and her appearances as an extra in

fourteen other episodes and Head.

She’d been doing such background work since the 1964 Hank Williams bio-pic Your Cheatin’ Heart. She was also a

stand-in for Barbara Eden on I Dream of Jeannie and Elizabeth Montgomery on Bewitched. Bert Schneider actually hired her to do that very job as Davy’s

stand in, though the union took issue with a woman standing in for a man. As a pretty slick consolation prize,

she got to actually appear on camera, making such an impression on viewers that

her reputation remains tied to The Monkees, though she also appeared in another

very sweet item: the “Sandman Cometh”/ “Catwoman Goeth” arc that gets my vote

for best Batman episodes.

Kairys has another interesting Monkees connection: she was

married to the late Nik Venet, who produced Mike Nesmith’s song “Different

Drum” for The Stone Poneys and was the brother of Steve Venet, who co-wrote

“Tomorrow’s Gonna Be Another Day” with Tommy Boyce (see H). More apocryphally, some have speculated that she inspired

Boyce & Hart to write the band’s final top-ten hit, “Valleri”. Even if that

songwriting duo wasn’t actually smitten enough with the extra to dedicate a

song to her, there’s no doubt that one guy was totally taken with Ms. Kairys:

Peter Tork confessed to having a huge crush on her during his commentaries on

Rhino’s old Monkees DVDs. Kairys, herself, got a chance to do the same when

she contributed new commentary tracks to “Monkees A La Mode” and “Some Like It Luke Warm” on the latest blu-ray

box set. In 2012, she appeared in “Breaking Bread”, a pro-frodis short for Funny or Die.com co-starring fellow Monkees serial-extra Roxanne Albee.

Keith Moon had his target shirt. Freddie Mercury had his diamond-print unitard. Ian Anderson had his codpiece. And Michael Nesmith had his wool hat. Perhaps the most iconic garment in pop history, Mike’s hat has a special history all its own. It all started when he came galumphing into his audition with a sack of laundry over one shoulder and a wool hat upon his pate. By Davy’s estimation, it made the intellectual Monkee look like some sort of mountain man. But we all have to wash our clothes and we all have to keep our heads warm, so cut Papa Nes some slack, Davy!

Nesmith’s green hat so enchanted Bob and Bert that they

actually considered naming his character “Wool Hat” in a move that would have

been even dumber than shortening the name Thorkleson to one that rhymes with

“dork.” Nes put his foot down about adopting that idiotic moniker, although he did briefly use it as an alias in the pilot episode, “The Royal Flush”, in which he is saddled with the silly screen name both when being himself in his anarchic interview with Rafelson and when in character, as Bing Russell’s manager, edited from the episode (see C), calls him “Wool Hat” (Mike is not the only Monkee with identity issues in the unaired version of “Here Come The Monkees”; Dolenz is credited as “Micky Braddock”, the screen name he used as a child when starring in his first TV series, Circus Boy). Nevertheless, Mike did

continue to wear a pom-pommed dome-cover throughout nearly every episode of

season one and often on stage during The Monkees’ tours of ’66 and ’67 (see T). Interestingly, the only album covers

that depict him in his signature cap are the eponymous debut and Bernard Yezsin’s illustration on the cover of Pisces, Aquarius, Capricorn, & Jones, LTD.

Mike was not as crazy about his hat as his fans were, so he

surely made himself and one young woman very happy indeed when he pulled the original off

his head and chucked it to her during a show at Cleveland’s Public Hall on

January 15, 1967 (contradicting rumors that he’d had the hat cast in bronze!). Nes

couldn’t be rid of the damn thing so easily, and he would soon be seen in a fresh hat of blue (unveiled in “Monkee Mother”, the first episode shot after the Public Hall gig) or a new green one

bedazzled with four buttons in mimicry of the band’s almost-as-iconic

double-breasted shirts (first worn in “It’s a Nice Place to Visit”). Mike’s hat remains a cultural force to this day, and you

can be sure that any blog article about The Monkees includes the comment

“That’s not even Michael Nesmith’s real hat!” posted by some joker who mistakes

the ability to quote The Simpsons for possessing original wit. Joke’s on you,

because it is his real hat.

Mike, Micky, Davy, and Peter had all tried to go the solo performer route before their days as Monkees. As each one departed, all four ex-Monkees attempted to continue their extra-Monkee musical careers with varying levels of success.

In late 1968, Peter was the first to go, and he quickly put

together a new group called Peter Tork And/Or Release with bassist Riley

Cummings (formerly of a group called The Gentle Soul) and drummer Reine Stewart

(who’d played on the 33⅓ Revolutions Per Monkee sessions

and later become Mrs. Tork). The band never managed to go anywhere, nor did a

six-song demo Peter recorded for Sire in 1980 featuring versions of “Shades of

Gray” and “Pleasant Valley Sunday”. Tork’s most enduring post-Monkees project

was a rock and blues band called Shoe Suede Blues, which began in the

mid-eighties and exists to this day. He also managed to slip out a proper solo

album called Stranger Things Have

Happened (featuring contributions from Dolenz and Nesmith) in 1994. Despite

synth-based arrangements that make it sound like it was recorded a decade

earlier than it was, there is some fine material on the record, such as the

title track and a much better version of “Getting’ In” than the one on Pool It!

Mike Nesmith left next in late 1969, and without question,

he enjoyed the most satisfying musical career after The Monkees. His first

album, Magnetic South recorded with

his First National Band, was an ingenious extension of his 1968 Nashville

sessions for The Monkees, using Sgt. Pepper’s-style

musical gimmicks (non-musical sound effects, segues, etc.) in a pure-country

setting. The album also produced a bona fide top-twenty-one hit called “Joanne”

featuring Nes’s previously unheard yodeling skills (so does the ass-kicking

album cut “Mama Nantucket”). Nes followed his debut with the similar though

still very good Loose Salute before

mixing things up more with eclectic albums such as the intimate And the Hits Just Keep on Comin’ (featuring

his solo rendition of “Different Drum) and the groundbreaking, award-winning,

synth-pop video album Elephant Parts on

his own Pacific Arts label. In 1994, Pacific Arts morphed into Rio Records

(named after the biggest hit on Elephant

Parts) and Nes released another four albums on Rio over the next twenty

years.

Although he was the voice of more Monkees hits than anyone

else, Micky Dolenz seemed less interested in a solo career than his former band

mates. In the seventies he recorded a number of singles for MGM (recently

compiled for the first time by +180 Records). Not until the nineties did Micky

start taking his solo career at least a little more seriously when he cut the

lullaby disc Micky Dolenz Puts You to

Sleep (bookended by new versions of the Monkees classics “Pillow Time” and

“Porpoise Song”) and an album of standards (“The Neverending Story” is a

standard? Awesome!) called Broadway Micky

for Kid Rhino. More recent releases include the Carole King tribute King

for a Day (featuring Dolenz fave “Sometime in the Morning”) and the Monkees-classic-loaded

live disc A Little Bit Broadway, A Little

Bit Rock & Roll.

As the face of The Monkees, Davy seemed most primed for solo

success. However, his 1971 eponymous album for Bell Records couldn’t even crawl

into the top two hundred. Its very Monkees-like single “Rainy Jane” just missed

the top fifty. Not even an appearance on The Brady Bunch to promote “Girl”

could rescue a solo career hampered by a contract that largely shut Davy out of

the creative process. The holiday themed Christmas

Jones faired no better, and Davy was left embittered by his time with the

label that would become Arista (see D).

He didn’t take a crack at the solo scene again until 1986’s Incredible Revisited, which was probably

intended to take advantage of the revived interest in The Monkees but was

ultimately flattened by Davy’s commitments to that band (see P). Davy managed to put out two more

studio discs—2001’s Just Me and

2009’s She—as well as several live

ones before his death in 2012.

So, assuming you are such an asshole (I’m kidding…you’re not

an asshole! I love you!), I offer one final argument: Frank Zappa loved The Monkees. Yes, kids, the guy who was known for

mercilessly lampooning pop commercialism and championing freedom of expression

thought The Monkees were A-OK. As I’m sure you’ll recall, when The Monkees were

allowed to invite their personal favorite talents to appear on the final few

episodes (Micky selected Tim Buckley and Davy chose future The Wiz composer Charlie Smalls), Mike

Nesmith dragged in the leader of The Mothers of Invention to swap

personalities, facial hair, and outfits (see W). This teaser for “The Monkees Blow Their Minds” ended up as one

of the series’ most anarchic moments, as Frank “played” a car by smashing it

with a sledgehammer while Mike conducted.

But was Frank Zappa done with The Monkees? Did their

cancellation and fall from public favor cause him to distance himself from his

former pop associates? Nope, because there he was again, towing a bull in Head and instructing Davy that it was the cute one’s duty to lead the way for the youth of today. Did it end there? Nope again. In

fact, Zappa even asked Micky to join the Mothers of Invention as drummer.

Accepting his own limitations on the instrument—and the fact that he was still

under contract with The Monkees— Dolenz declined despite being flattered that

such a respected musician and composer thought so highly of his abilities. He’s

not the only one, Micky! Much love to you and the rest of The Monkees on this

momentous day!